Abstract

The following article highlights both high and mid level concepts toward creating a simple release pipeline for PowerShell modules. The major focus will cover file structure, test practices, task runners, and portability between CI/CD systems. Additional topics include generated reports, design patterns for code consistency, and a Jenkins CI implementation. The supplementary project: Xainey/PSHitchhiker is available on Github to analyze alongside the project.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Planning

- Project Structure

- Create Tasks

- Other Design Considerations

- Case Study: Jenkins

- Conclusion

- References

- Changelog

Introduction

PowerShell has been a surprisingly fun and straightforward language to learn.

That being said, it has also greatly evolved since the earlier versions.

As I first started learning the language, I followed advice and examples from some of the earliest posts on Hey, Scripting Guy!, StackOverflow and other TechNet boards.

As a newfound chef in the PowerShell kitchen, I was cooking up spaghetti code by the truckload.

Once maintainability turned into a nightmare I started making reusable modules, DSC resources, and bite size scripts.

The DSC community taught me a ton about testing and style guidelines.

In the beginning, I thought it was a great idea to pipe together 50 lines of code filled with aliases. Play: CodeGolfClap.mp4

After scripting for a few months, It’s time to start creating modules. How hard could it be? I was lost in the details here for a while. You need this intimidating module manifest and half a dozen other CI tools to publish to the PowerShell Module Gallery. MSDN documentation varied a ton and community projects on GitHub were all structured slightly different. Eventually, you come to understand how the entire process works. However, with everyone making their own path, you still have to take the time to figure out each author’s repository and code structure.

I wanted to make an “Ideal” project structure for my team. “Here is the way we will build all of our projects.” Now, if we bring in developers new to PowerShell, it gives them the boilerplate to hit the ground running. In the beginning, we pretty much wear Google and StackOverflow out and code sling our way to success.

Inspiration

The following article is based on a few key sources.

The Release Pipeline Model by Michael Greene and Steven Murawski is an amazing primer for beginners and experts alike. This whitepaper gives incredible insight toward explaining a release pipeline, CI/CD methodologies, and how we begin to remove the wall between development and operations.

Greene and Murawski go on to define what a release pipeline looks by identifying 4 stages:

- Source

- Build

- Test

- Release

I’ve spent over a year teaching and growing my team’s roots in (1. Source) alone. Having all of our projects, configuration, documentation, etc. stored in Git is massive. This step alone collects and tracks changes on all of our projects. It gives us a single location to assess our projects once we are prepared to begin on #2-4. Once we started working on building pipelines the concept was one thing but the implementation was foreign.

Our pipeline ideas hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don’t.

Enter Brandon Olin with his blog post on Building a Simple Release Pipeline. This guide takes you by the hand and teaches you how to make something on your own. Remember the proverb, “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime?” Brandon did this, except instead of fish we are talking DevOps.

Our final primer comes from Warren Frame’s guide on Building a PowerShell Module. This is one of the best documented examples avaliable. We will borrow greatly from these examples.

A common mistake that people make when trying to design something completely foolproof is to underestimate the ingenuity of complete fools. Douglas Adams

Planning

We start by creating a list of project requirements, dependencies, and build pass criteria.

Requirements

Create a Clean Project Structure

- We want to make a repo for a PowerShell module that can be used for company internal or community projects.

- The repo should keep files to a minimum.

- The structure should be clean and recognizable for every project.

Attempt to Meet Code Style Requirements

- Enforces projects strive to keep in accordance with community code style and best practice recommendations.

- Drives consistency between multiple developers and projects.

Make the Project Easly Transferable Between CI systems

- Use PowerShell to abstract all of the heavy liftings (common tasks).

- To move this project between CI systems we should only need to add basic CI configurations files.

- (e.g.,

appveyor.yml,travis.yml,Jenkinsfile).

- (e.g.,

Enforce Build Pass Requirements

- The Build should only pass if each compliance criterion has been met.

- (e.g., 0 Failed tests, 0 Lint Errors, 50% Code Coverage).

Dependencies

These may vary from project to project. Here we attempt to establish the dependencies mandatory for every project.

Mandatory

Optional

Build Pass Criteria

Next, we determine each of the requirements needed to allow a build to pass before deploying to production.

Passing Tests

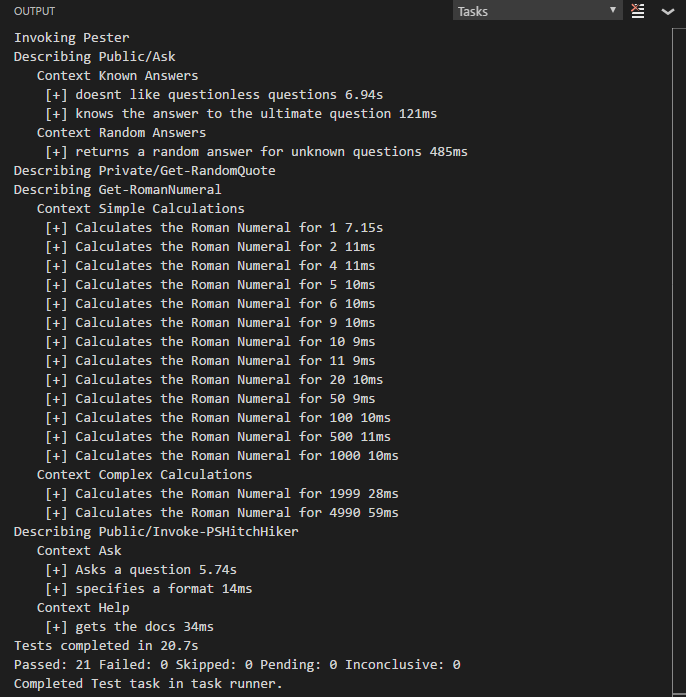

Pester is the PowerShell test framework used for testing. Pester returns test results, timing, metrics, and code coverage.

We use a TDD approach: Red -> Green -> Refactor to develop locally.

Units tests should be green before pushing back to master; Good is green, no exception!

Enforcement:

- The Build should always fail if any unit tests fail.

Coverage Compliance

Coverage shows us percentages of code that has been tested. Low coverage indicates that very little code has been backed with tests. This warns us that there is a high possibility of regression bugs. While high coverage is certainly preferred, 100% coverage is often unrealistic.

Enforcement:

- Default: 0% Coverage.

- For most projects, we will set this to ~80%.

A few concepts on testing/coverage:

- 100% line coverage does not mean you will have 100% branch coverage.

- Integration testing helps to pick up gaps missed by unit testing.

- 100% coverage can indicate “Cheating” or low-quality tests to achieve coverage.

Passing Linting Rules

PSScriptAnalyzer is the Linter used for PowerShell. Only two types of errors are returned from the Linter: Errors, and Warnings.

Enforcement:

- The Build should always fail on errors.

- The Build should always fail on warnings.

Suppression rules can be used to mask warnings if the code design strictly cannot avoid the Lint error.

Questions

Two of the essential questions when looking to create a new PowerShell Project:

How do you scaffold a new project?

Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything PowerShell

- Plaster may become the de facto method.

- Example: Plaster New Module

- Clone an existing Git project or template

- Offers the best transparency.

- Helper function

- A few people like to create helper functions to scaffold new projects.

What are the community standards/guidelines?

- Code Style Guidelines are a great place to start to drive team consistency.

- Microsoft offers some of their own DSC Style Guidelines that are worth a look.

Project Structure

New Repository

For this example project, we will be creating a simple module to answer the Ultimate Question. This module will be called PSHitchhiker.

Add Essentials

The first step is to scaffold a project.

In this section, we will discuss the structure and components of the repository.

I find it a bit easier to examine the structure of a project in bite-sized pieces instead of large chunks.

To illustrate this, we will create the scaffolding by hand with our PowerShell prompt.

Don’t Panic. I’ve added a touch command to my PowerShell $Profile to appease my Mac habits.

First, we create base folders and files for Git.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | PS C:\Code> mkdir PSHitchhiker PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> cd PSHitchhiker PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> mkdir PSHitchhiker PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> mkdir tests PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch Readme.md PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch Licence PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch .gitignore PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> git init |

Now we have something as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── PSHitchhiker/ <--- "Src" ├── tests/ ├── Readme.md ├── .gitignore └── Licence |

Ideally, we keep this structure as clean and minimal as possible.

Here the Src folder is everything to actually run the module, therefore we give it the same name as our root repo directory: PSHitchhiker.

For people not using package management (i.e. Install-Module), the Src folder could be copied directly to one of the registered $PSModulePath locations.

1 2 | # View Registered Module Paths $env:PSModulePath -Split ';' |

Add Build Tools

Next, we add some files for our task runner (Invoke-Build). After examining some of the scaffolding examples from Plaster, I decided to add a settings file as well. These two files will be the core entry point of our pipeline no matter which CI solution we decide to use.

1 2 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── PSHitchhiker/ ├── tests/ ├── Readme.md ├── .gitignore ├── Licence ├── PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 <--- "Build Tasks" └── PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 <--- "Build Settings" |

Add Help Files

Next, we want to make sure we include a help document for our module.

Charge the localization lasers, en-US speakers quickly approaching on the starboard side.

1 2 3 4 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> cd PSHitchhiker PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> mkdir en-US PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> cd en-US PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker\en-US> touch about_PSHitchhiker.help.txt |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── PSHitchhiker/ │ └── en-US/ <--- "Locale Directory" │ └── about_PSHitchhiker.help.txt <--- "Help Document" ├── tests/ ├── Readme.md ├── .gitignore ├── Licence ├── PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 └── PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 |

Add Manifest and Root Module

Now we add in our Module Manifest and root module file. Here we add very little detail since this is easier to edit with a text editor.

1 2 3 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> touch PSHitchhiker.psm1

PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> New-ModuleManifest -Path "PSHitchhiker.psd1"

-RootModule "PSHitchhiker.psm1" -Author "Michael Willis" -Description "..."

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── PSHitchhiker/ │ ├── en-US/ │ │ └── about_PSHitchhiker.help.txt │ ├── PSHitchhiker.psd1 <--- "Module Manifest" │ └── PSHitchhiker.psm1 <--- "Root Module" ├── tests/ ├── Readme.md ├── .gitignore ├── Licence ├── PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 └── PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 |

Add Private and Public Folders

Next, we add in folders for private and public scripts.

- Private scripts are used by the module and should not be exposed or accessible outside of the module.

- Public scripts should be exposed and accessible outside of the module.

1 2 3 4 5 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> mkdir Private PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> mkdir Public PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker> cd ../tests PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\tests> mkdir Private PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\tests> mkdir Public |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── PSHitchhiker/ │ ├── en-US/ │ │ └── about_PSHitchhiker.help.txt │ ├── Private/ <--- "Private Src" │ ├── Public/ <--- "Public Src" │ ├── PSHitchhiker.psd1 │ └── PSHitchhiker.psm1 ├── tests/ │ ├── Private/ <--- "Private Tests" │ └── Public/ <--- "Public Tests" ├── Readme.md ├── .gitignore ├── Licence ├── PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 └── PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 |

Now with this structure, we are able to load all of our module scripts by using dot sourcing. PSCookieMonster and Mike F. Robbins both have great examples of this technique.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | # File: PSHitchhiker.psm1 $Public = @( Get-ChildItem -Path $PSScriptRoot\Public\*.ps1 -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue ) $Private = @( Get-ChildItem -Path $PSScriptRoot\Private\*.ps1 -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue ) foreach($import in @($Public + $Private)) { try { . $import.fullname } catch { Write-Error -Message "Failed to import function $($import.fullname): $_" } } Export-ModuleMember -Function $Public.Basename |

Add CI Flavor of Choice

Now we add a config file for our CI runner. In this example, we will be using a Jenkins config file, but we could easily add an endpoint for AppVeyor, Travis, TFS, etc.

1 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> touch Jenkinsfile |

1 | <--- "Such CI. So Groovy. Wow." |

Further Improvements

By this point, the base skeleton is pretty solid for a generic module.

Possible additions:

- Release Notes

- *.psdeploy.ps1

- lib/

- bin/

- PSHitchhiker.Formats.ps1xml

Organizing Tests

Taking a slight aside to talk about tests – or at least my concerns.

There is little consistency on how the community organizes their tests on GitHub.

Why is this a problem?

Testing provides us with a great form of living documentation. This value diminishes as it becomes harder for us to figure out the organization and connection between tests and source. With the proper organization, the file system itself helps indicate which files have and have not been tested (without running Pester).

Developing using BDD/TDD practices with other languages I found myself respecting the guideline:

Make the Test structure match the Source structure

Example 1: Matching Source and Tests

If we have a script in our source directory we should create a script with the same name, in the same location in the respective tests folder.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | Repo/ ├── src/ │ ├── A.ps1 <--- "Script" │ └── Deeper │ └── B.ps1 └── tests/ ├── A.Tests.ps1 <--- "Test" └── Deeper └── B.Tests.ps1 |

Example 2: Leave Room for Integration Tests

For the scope of this article, we will only focus on unit testing. In the future, something like Test Kitchen could be used for integration testing.

The following example almost matches the test/source 1-to-1 mapping. Here we add one additional layer under tests to separate unit and integration tests.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | MyModule/ ├── readme.md ├── src/ │ └── MyModule.ps1 <--- "Script" └── tests/ ├── unit/ │ └── MyModule.Tests.ps1 <--- "Unit Test" └── integration/ └── MyModule.Tests.ps1 <--- "Integration Test" |

Example 3: Strict Pattern

A more strict option may look like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | MyModule/ ├── readme.md ├── src/ │ └── MyModule.ps1 ├── tests/ │ └── MyModule.Tests.ps1 └── integration/ └── MyModule.Tests.ps1 |

For this project, we will use Example 3.

By using Example 3, we are able to assume where the source for the unit test is located (Line 5).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | $here = Split-Path -Parent $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path $sut = (Split-Path -Leaf $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path) -replace '\.Tests\.', '.' # Since we match the srs/tests structure we can assume: $here = $here -replace 'tests', 'PSHitchhiker' . "$here\$sut" # Import our module to use InModuleScope Import-Module (Resolve-Path ".\PSHitchhiker\PSHitchhiker.psm1") -Force # Use InModuleScope to gain access to private functions InModuleScope "PSHitchhiker" { Describe "Public/Ask" { # "Folder/File" # ... Context/It Statements } } |

Create Tasks

Whether we are running pipeline tasks locally with PowerShell or leveraging a CI system, we use Invoke-Build as a common entry point. This allows us to leverage any CI system without changing the underlying pipeline functionality and portability.

Invoke-Build 101

The Invoke-Build module is a new alternative to PSake, it is well documented and frequently updated.

The following are simplified examples to illustrate the ease of use.

Example 1: Invoke-Build -Task

An Invoke-Build Task has the following format:

1 2 3 4 | # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory task Clean { ... } |

A task can be called by name:

1 | PS C:\> Invoke-Build -Task Clean |

Example 2: Pre/Post Chaining

Like PSake, we can define tasks to run additional tasks before and/or after.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory task Clean BeforeClean, { # ... }, AfterClean # Synopsis: Executes before the Clean task task BeforeClean { # ... } # Synopsis: Executes after the Clean task task AfterClean { # ... } |

Example 3: View All Tasks

To view a list of available tasks, run the following command:

1 | PS C:\> Invoke-Build ? |

This command yields the following output:

1 2 3 4 5 | Name Jobs Synopsis

---- ---- --------

BeforeClean {} Executes before the Clean task

AfterClean {} Executes after the Clean task

Clean {BeforeClean, {}, AfterClean} Clean Artifacts Directory

|

The Synopsis is generated from the code comments defined directly before the task.

1 | # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory

|

Example 4: Default Task

The default task is indicated with a period: ..

It’s best to add one for verbosity, otherwise, Invoke-Build starts using alternative logic to determine the default.

1 2 3 | task . { # ... } |

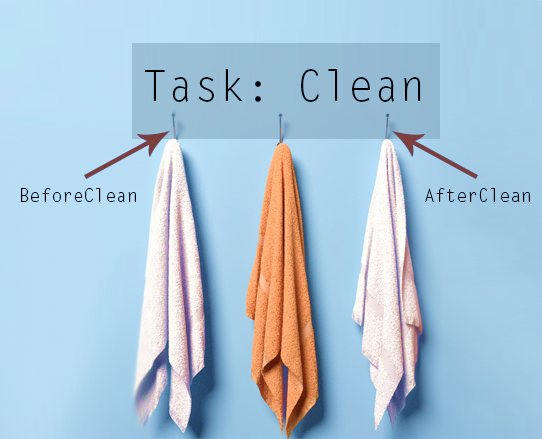

Using Hooks

I stumbled across an example of hooks in Plaster and loved the idea. This reminded me a lot of using WordPress Hooks. In WordPress, this was a way for core and plugin authors to designate places in their code for others to inject custom code. These injection points allow other developers to modify the workflow without modifying the core programming.

In the above image, the core library contains a function/task called Clean.

Three hooks are registered to allow a 3rd party plugin to inject custom code at the beginning, middle, and end of the function.

To create something similar in PowerShell with Invoke-Build, we create our core function Clean in PSHitchhiker.build.ps1.

1 2 3 4 | # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory task Clean BeforeClean, { # ... }, AfterClean |

Next, in PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 we add blank placeholders for these tasks that can be customized when needed.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | ############################################################################### # Before/After Hooks for the Core Task: Clean ############################################################################### # Synopsis: Executes before the Clean task. task BeforeClean {} # Synopsis: Executes after the Clean task. task AfterClean {} |

Update: Thanks to Roman Kuzmin (@romkuzmin) for demonstrating a better way to add hooks.

By using the flags -Before and -After, we do not need to define our hook tasks unless we plan on implementing them.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | ############################################################################### # PSHitchhiker.build.ps1, Note that we do not have to pre-define/inject hooks ############################################################################### # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory task Clean { # ... } ############################################################################### # PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1, Note that we do not have to define dummy hooks ############################################################################### # Synopsis: Executes before the Clean task. # task BeforeClean -Before Clean {} # Synopsis: Executes after the Clean task. # task AfterClean -After Clean {} |

Creating Tasks for Pipeline

To create our build scripts we will use a few files. The following code examples in this section are to illustrate the logic. The full implementation can be viewed on GitHub.

Files

- PSHitchhiker.build.ps1

- Include definitions for all core tasks.

- PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1

- Include all of our hook tasks, custom settings, and build parameters.

- build_utils.ps1

- Includes all of the generic helper functions used to simply the PSHitchhiker.build.ps1 file.

Dependencies

There are many ways to manage dependencies such as making your PSake or Invoke-Build build install the prerequisites.

One method may be to simply add a dependencies task.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | # Synopsis: Install Build Dependencies task InstallDependencies { # Cant run an Invoke-Build Task without Invoke-Build. Install-Module -Name InvokeBuild -Force Install-Module -Name DscResourceTestHelper -Force Install-Module -Name Pester -Force Install-Module -Name PSScriptAnalyzer -Force } |

Since the above causes a chicken-egg situation we would need to manually install Invoke-Build first.

This usually means we create yet another file like Build.ps1 to install dependencies before calling Psake or Invoke-Build.

A few of us have toyed with ideas on dependency management. One of the newer plausible solutions is PSDepend. In any situation, we have to bootstrap installing at least one module before we can install the rest.

Clean

The Clean task will ensure we have a clean directory to store build artifacts.

Tasks in the pipeline will use this Artifacts directory to output test results, reports, archives, and packages.

- Artifacts Directory:

- Since there may be existing artifacts from previous builds we delete everything in this folder.

- If this folder does not exist we create it.

- This directory will be added to

.gitignore

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | # Synopsis: Clean Artifacts Directory task Clean BeforeClean, { if(Test-Path -Path $Artifacts) { Remove-Item "$Artifacts/*" -Recurse -Force } New-Item -ItemType Directory -Path $Artifacts -Force # Temp: Clone since this project is not currently available through PackageManagement & git clone https://github.com/Xainey/PSTestReport.git }, AfterClean |

Analyze

After performing a Clean step, we run PSScriptAnalyzer to lint the source code.

At this early stage, we just fail the build if there are any errors or warnings.

There is not much gain to let the build progress further unless we want to create early stage artifacts.

We could easily alter this task to make it only fail on errors.

- Lint the Code with PSScriptAnalyzer

- Save Results as

JSON - Fail the Build on error: by using throw.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | # Synopsis: Lint Code with PSScriptAnalyzer task Analyze BeforeAnalyze, { $scriptAnalyzerParams = @{ # ... } $saResults = Invoke-ScriptAnalyzer @scriptAnalyzerParams # Save Analyze Results as JSON $saResults | ConvertTo-Json | Set-Content (Join-Path $Artifacts "ScriptAnalysisResults.json") if ($saResults) { $saResults | Format-Table throw "One or more PSScriptAnalyzer errors/warnings where found." } }, AfterAnalyze |

Test

After linting the code with the Analyze step, we run the unit tests.

This step could simply run Invoke-Pester against all of the unit tests and fail.

However, for reporting the results on a CI system, we need to run the tests and publish the results before the build fails.

To achieve this, we split the Test task into two tasks: RunTests and ConfirmTestsPassed

1 2 | # Synopsis: Run/Publish Tests and Fail Build on Error

task Test BeforeTest, RunTests, ConfirmTestsPassed, AfterTest

|

RunTests

Now, when we run Invoke-Pester we save the test results to NUnit.xml as well as .json to include the code coverage metrics.

- Run Unit tests

- Run Code Coverage (during Invoke-Pester call)

- Save Results to

NUnit XML(during Invoke-Pester call) - Save Results to

JSON - Generate Test Report

- Do Not Fail if tests fail

- Do Not Fail if code coverage is not met

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | # Synopsis: Test the project with Pester. Publish Test and Coverage Reports task RunTests { $invokePesterParams = @{ # ... } # Publish Test Results as NUnitXml $testResults = Invoke-Pester @invokePesterParams; # Save Test Results as JSON $testresults | ConvertTo-Json -Depth 5 | Set-Content (Join-Path $Artifacts "PesterResults.json") # Temp: Publish Test Report $options = @{ #... } . ".\PSTestReport\Invoke-PSTestReport.ps1" @options } |

ConfirmTestsPassed

After the unit tests are run and recorded, we read our TestResults.XML file and check if any of the unit tests have failed.

If any of the tests fail then we fail the build using assert.

Next, we check the code coverage, if the coverage is not up to a certain percent we can also fail the build.

This could be used to enforce a set percent of test coverage on code before it is piped into production.

- Get Pester results from NUnit XML

- Fail the Build if any tests fail

- Get Pester results from JSON (for coverage)

- Fail the Build if coverage is not compliant

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | # Synopsis: Throws and error if any tests do not pass for CI usage task ConfirmTestsPassed { # Fail Build after reports are created, this allows CI to publish test results before failing [xml] $xml = Get-Content (Join-Path $Artifacts "TestResults.xml") $numberFails = $xml."test-results".failures assert($numberFails -eq 0) ('Failed "{0}" unit tests.' -f $numberFails) # Fail Build if Coverage is under requirement $json = Get-Content (Join-Path $Artifacts "PesterResults.json") | ConvertFrom-Json $overallCoverage = [Math]::Floor(($json.CodeCoverage.NumberOfCommandsExecuted / $json.CodeCoverage.NumberOfCommandsAnalyzed) * 100) assert($OverallCoverage -gt $PercentCompliance) ('A Code Coverage of "{0}" does not meet the build requirement of "{1}"' -f $overallCoverage, $PercentCompliance) } |

Archive

Now that the tests have passed and reports have been created, we create some archived bundles for our CI artifacts. I’m borrowing from some of the DSC helper scripts to build the NuGet packages.

- Create

.zipArchive - Create

.nupkgArchive

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | # Synopsis: Creates Archived Zip and Nuget Artifacts task Archive BeforeArchive, { $moduleInfo = @{ # ... } Publish-ArtifactZip @moduleInfo $nuspecInfo = @{ # ... } Publish-NugetPackage @nuspecInfo }, AfterArchive |

Publish

The last step is to publish my module to a repository to be able to leverage PackageManagement commands such as Install-Module.

For this task, we are going to use an SMB share instead of a NuGet server.

- Publish Module (using SMB repo)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | # Synopsis: Publish to SMB File Share task Publish BeforePublish, { $moduleInfo = @{ # ... } Publish-SMBModule @moduleInfo -Verbose }, AfterPublish |

If we want to install a module from this SMB share to another machine, we will need to register the repo.

1 | Register-PSRepository -Name "AcmeCorp" -SourceLocation "\\Server01\Repo" -InstallationPolicy Trusted |

Afterward, we use the -Repository flag on PackageManagement commands.

1 2 | Find-Module -Repository "AcmeCorp" Install-Module -Name "PSHitchhiker" -Repository "AcmeCorp" |

Default Task

This task is called by simply running Invoke-Build from the project root.

If running this directly from a development machine the Build Number will default to 0 unless specified.

1 2 | # Synopsis: Run full Pipleline.

task . Clean, Analyze, Test, Archive, Publish

|

Other Design Considerations

Manage Version Numbers

Each module has 3 numbers in its version. For this project, we will call these major, minor, and build.

- We control the major and minor number in the module manifest.

- The build number will correspond to the build number of the CI system.

The build number will use $env:BUILD_NUMBER and can be overwritten by specifying a -BuildNumber switch when calling Invoke-Build.

1 2 | # Example Invoke-Build -Task Publish -BuildNumber 10 |

Single Point of Access

The following pattern helps keep all of the exposed CLI commands all in one place.

- First, we add only one function per file.

- Second, we make the filename match the function it represents.

Next, in the public folder, will create Invoke-PSHitchhiker.ps1 which will be exposed as a CLI point of access.

- The ParamaterSetName will always be the name of a file in the private folder.

- We remove the ParamaterSetName from the

$PSBoundParametersand splat the result to call the private function.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | function Invoke-PSHitchhiker { [cmdletbinding(DefaultParameterSetName="Help")] param( # Help [Parameter(Mandatory=$False, ParameterSetName="Help")] [switch] $Help, # Ask [Parameter(Mandatory=$True, ParameterSetName="Ask")] [switch] $Ask, [string] $Format, [Parameter(Mandatory=$True, ParameterSetName="Ask", Position=0)] [string] $Question ) # Remove Switch for ParmameterSetName $PSBoundParameters.Remove($PsCmdlet.ParameterSetName) # Call Functon with Bound Parms . $PsCmdlet.ParameterSetName @PSBoundParameters } |

As seen in the example, we can also use advanced cmdletbinding techniques such as positional parameters.

VS Code Bandwagon

1 2 3 4 | PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> mkdir .vscode PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker> cd .vscode PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\.vscode> touch tasks.json PS C:\Code\PSHitchhiker\.vscode> touch settings.json |

1 2 3 4 5 | PSHitchhiker/ ├── .vscode/ │ ├── tasks.json │ └── settings.json └── ... |

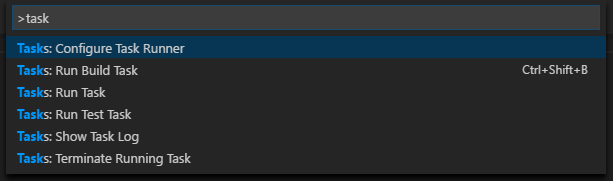

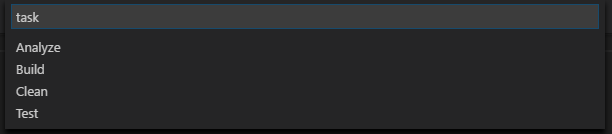

Tasks.json

The great thing about VS Code is how easy it is to integrate tasks into the editor with a tasks.json file.

Press F1 and type: task. Here we can run a build task easily with Ctrl+Shift+B

If we dig into this deeper by choosing Tasks: Run Task we see all of the custom tasks in our tasks.json

The following is an example of running a Pester test task in VS Code.

Settings.json

The settings is another one of my favorite project customizations.

In this example, we make sure our team members remove trailing whitespaces on save and we tell VSCode to automatically scrub our Jenkinsfile as Groovy.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | { "files.trimTrailingWhitespace": true, "files.associations": { "Jenkinsfile": "groovy" } } |

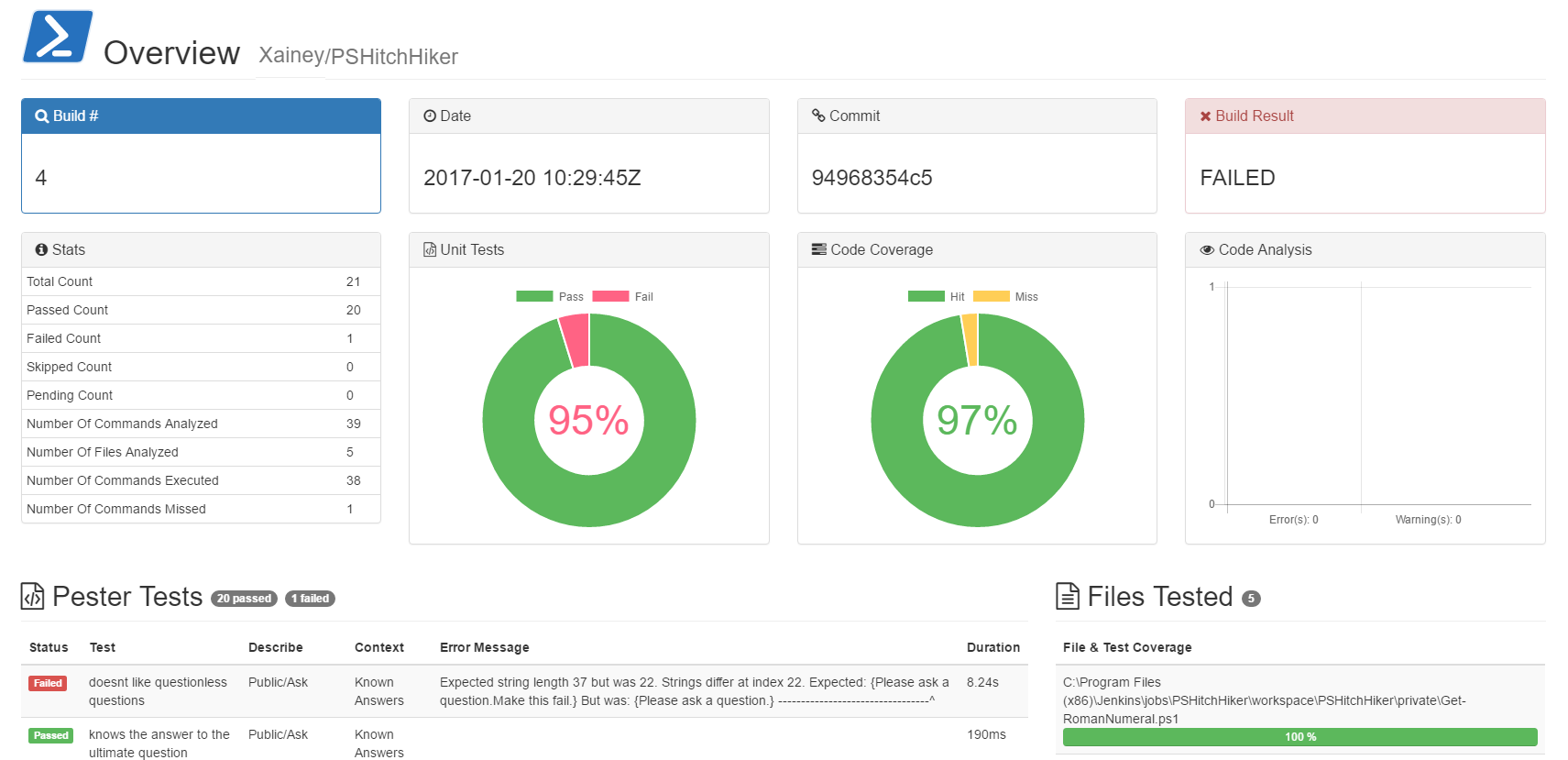

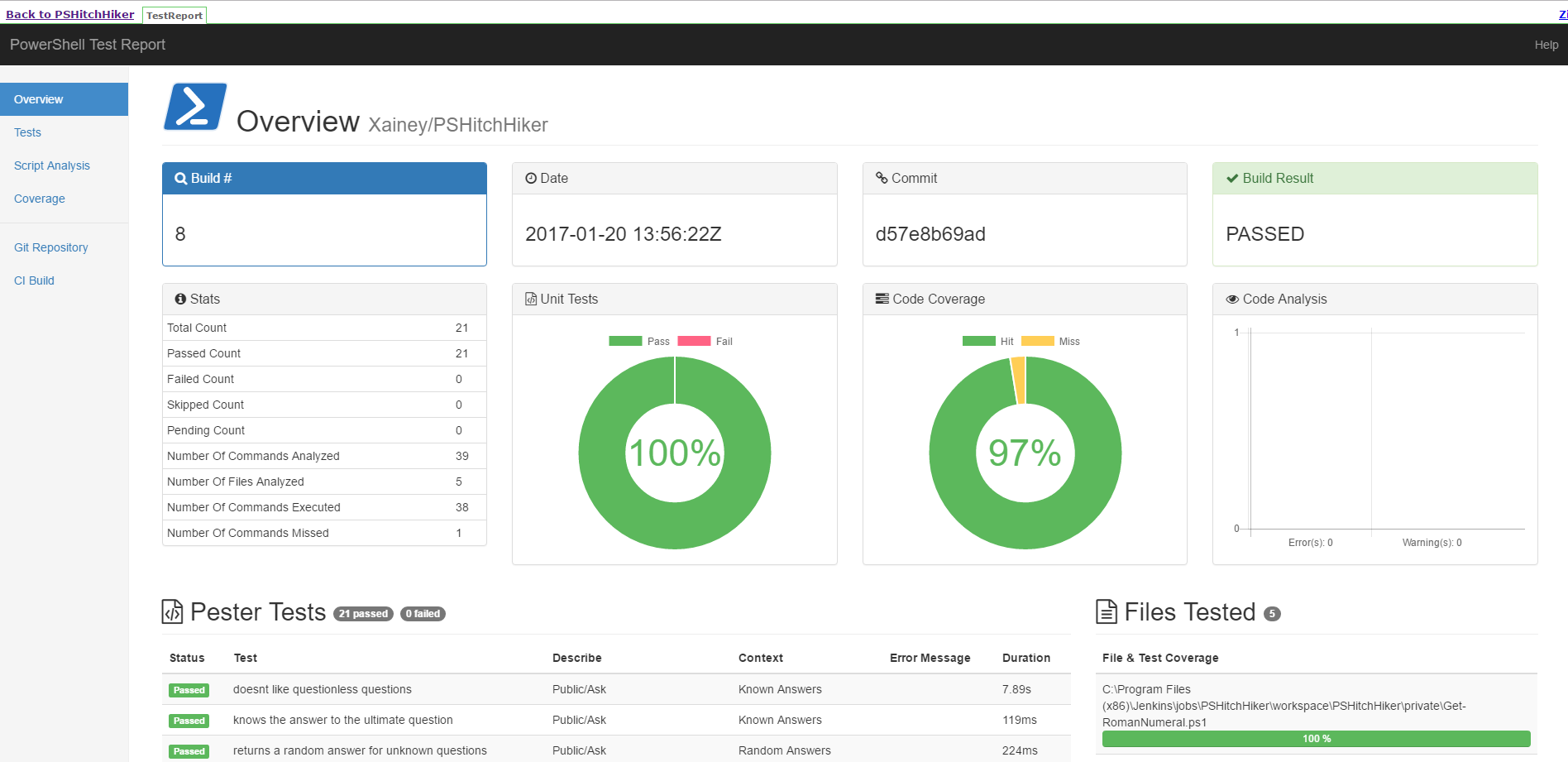

Reporting

After looking at a handful of the community generated reports I decided to create my own. Its still an early work in progress and can be found on Github at Xainey/PSTestReport.

Concept

Main Content

- Tests

- Failed

- Passing

- Coverage

- Overall

- Per file

- Linter

- Errors

- Warning

- Build Meta

- Build Number

- Timestamp

- Commit Hash

- Build Status

- Pester Stats

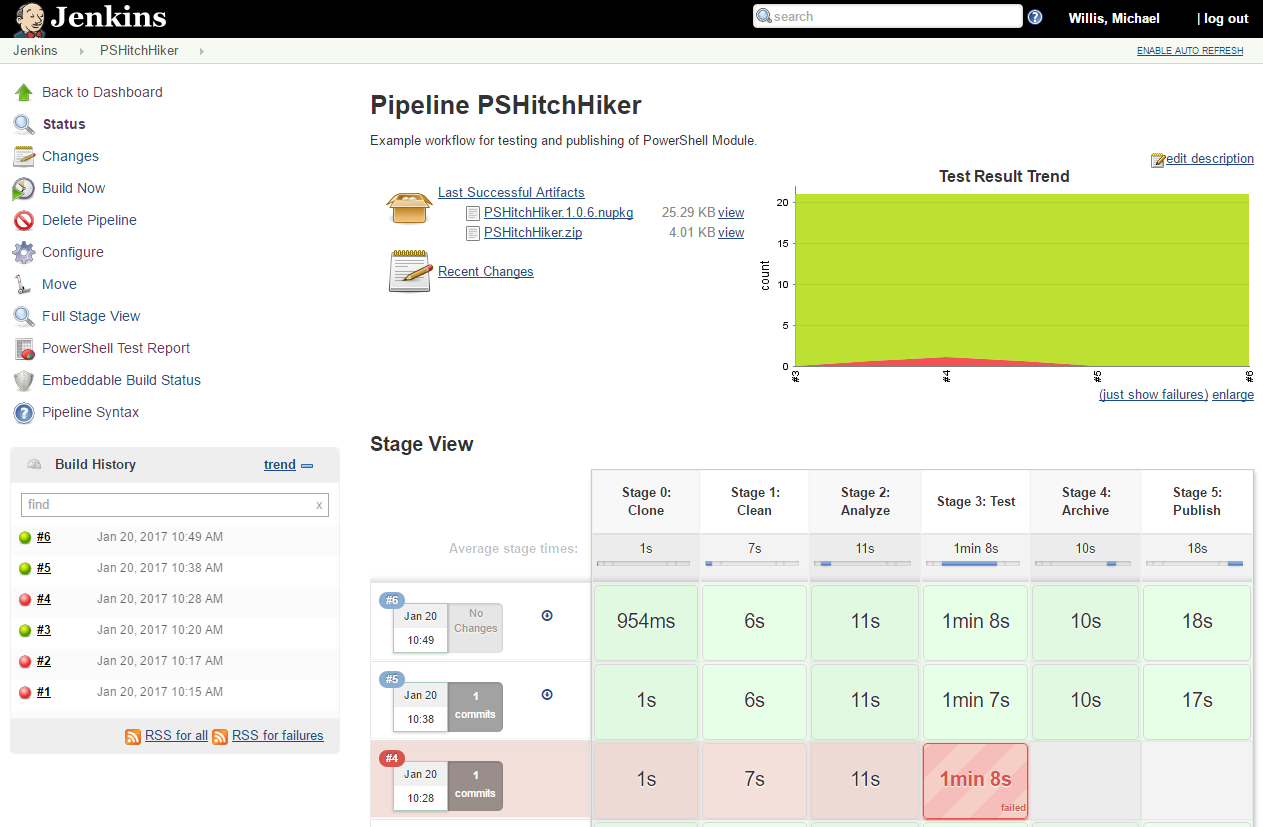

Case Study: Jenkins

WebHooks / CRON Polling

To have our Jenkins job trigger automatically, we set up webhooks on our Git repository. Our hook will tell Jenkins to kick off the job if someone pushes to master or creates a pull request. Webhooks are a great way to reduce the manual time needed to run the build and help keep the WIP flowing for teams working on the same code base.

Alternatively, Jenkins can poll a Git repo on CRON schedule, but this is not recommended. If the schedule is too frequent you suffer from performance and if the gap is too large your workflow is no longer continuous.

For a moment, nothing happened. Then, after a second or so, nothing continued to happen.

Plugins

The following is a list of the non-stock plugins I’ve used in the demonstration images.

DSL Pipeline

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | // Stages stage('Stage 0: Clone') stage('Stage 1: Clean') stage('Stage 2: Analyze') stage('Stage 3: Test') stage('Stage 4: Archive') stage('Stage 5: Publish') |

Build Dashboard

Seen Features:

- Downloads for

.nupkgand.zipartifacts - Test trend from published Pester

NUnit.xmltests - Stage view from

Jenkinsfile - Custom

Powershell Test Reporton the side navigation

Helper Functions

For running PowerShell commands in our Jenkinsfile we create a helper function.

1 2 3 4 | // Helper function to run PowerShell Commands def posh(cmd) { bat 'powershell.exe -NonInteractive -NoProfile -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -Command "& ' + cmd + '"' } |

This is a workaround since PowerShell plugin does not yet have pipeline support.

Call Invoke-Build With Pipeline

1 2 | // Call Groovy function posh 'Invoke-Build -Task Test' |

Use Classes To Keep Variables at Top

Simular to how we used PSHitchhiker.settings.ps1 to isolate all of our configuration variables, we use Groovy Global class at the top of our Jenkinsfile.

There are other alternatives such as using groovy.transform.Field and the @Field annotation.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | // Config class Globals { static String GitRepo = 'http://github.com/xainey/PSHitchhiker.git' static String MyVar = 'Hello' static String MyOtherVar = 'Human' } node('master') { stage('Stage 0: Clone') { git url: Globals.GitRepo } // ... } |

Publish Test Reports

As earlier discussed, we need Jenkins to do fail Stage 3: Test if our pester tests fail.

However, we want to make sure that our tests and HTML reports are published first.

- Run Invoke-Build

RunTeststask to generate test files - Publish the

.NUnitXmlresults to the NUnit plugin - Publish the

PowerShell Test Reportwith HTMLPublisher plugin - Run Invoke-Build

ConfirmTestsPassedtask to check if this stage should fail

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | stage('Stage 3: Test') { // Run Tests posh 'Invoke-Build RunTests' // Publish Tests to Jenkins step([$class: 'NUnitPublisher', // ... ]) // Publish Custom Test Report publishHTML (target: [ // ... ]) // Force build to fail if any tests failed. posh 'Invoke-Build ConfirmTestsPassed' } |

Security

To allow Jenkins to run inline CSS and JavaScript in the HTML Report we will need to configure the Content Security Policy.

Currently, I’m simply adjusting the policy on my test server under Manage Jenkins > Script Console:

1 2 3 | // CSP Examples System.setProperty("hudson.model.DirectoryBrowserSupport.CSP", "style-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline';") System.setProperty("hudson.model.DirectoryBrowserSupport.CSP", "") |

These settings do not persist when Jenkins is restarted. They can be added to the JAVA_ARGS for startup as seen in this StackOverflow Comment.

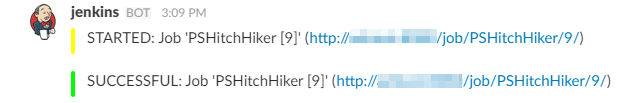

ChatOps

When our Jenkins server kicks off builds, we want to inform our team when a build starts and completes. This can be done by messages via email or chat applications like Slack and Hipchat. By integrating automated communication in our pipeline, we provide a real-time activity stream to our team.

Helper Script

Borrowing from a blog post on Cloudbees, we choose to add Slack support to our pipeline.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | // Helper function to Broadcast Build to Slack def notifyBuild(String buildStatus = 'STARTED') { buildStatus = buildStatus ?: 'SUCCESSFUL' def colorCode = '#FF0000' // Failed : Red if (buildStatus == 'STARTED') { colorCode = '#FFFF00' } // STARTED: Yellow else if (buildStatus == 'SUCCESSFUL') { colorCode = '#00FF00' } // SUCCESSFUL: Green def subject = "${buildStatus}: Job '${env.JOB_NAME} [${env.BUILD_NUMBER}]'" def summary = "${subject} (${env.BUILD_URL})" slackSend (color: colorCode, channel: "${Globals.JenkinsChannel}", message: summary) } |

Using NotifyBuild

All our stages should be wrapped in a try/catch/finally block.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | // Workflow Steps node('master') { try { notifyBuild('STARTED') // Example Stages stage('Stage 0: Clone') { } } catch (e) { currentBuild.result = "FAILED" throw e } finally { notifyBuild(currentBuild.result) } } |

Conclusion

Going from concept to an example has been challenging. Hopefully, my disjointed thoughts will prove helpful. My initial goal was to create a base structure that would work for any public or private module project. A lot of work is still needed. I would love to build up some integration testing to add to this project.

There are still gaps and details that I have not covered, such as using C#, .dlls, certificates, etc. I am completely open for suggestions, improvements, and PRs. What do you like and what could be done better?

So long and thanks for all the fish shares!

References

- Release Pipeline

- Building a Simple Release Pipeline

- Invoke-Build

- PowerShellPracticeAndStyle

- DSC Style Guidelines

- Plaster

- PSScriptAnalyzer

- PSScriptAnalyzer Suppress

- Pester

- PSDeploy

- FunctionScaffold

- BuildingAPowerShellModule

- PlasterNewModule

- DotSourcing

- Jenkins-Nunit

- Jenkins-HTML

- Jenkins-Slack

- Jenkins-ChatOps

- WordPressHooks

- PlasterHooks

- TestKitchen

- ModuleManifest

- VSCode

- Jenkins-EmbeddableBuild

- Jenkins-GreenBalls

- Jenkins-CSP

- SO-JenkinsCSP

- build-ps1

- PSDepend

- PSHitchhiker

- PSTestReport

Changelog

- 2017-01-27

- Update Invoke-Build documentation on before/after Hooks to address Issue-1.